By Jeanne F. Neath

If you had the choice, wouldn’t you rather live in a woman-centered economy?[1] It’s pretty clear by now that the male-dominated economy – patriarchal capitalism – is a social, ecological and economic failure. What if I told you that there is a choice? Most people don’t realize it, but everyone participating in the global economy is living in two economies, a mix of economies where one is male-dominated and the other female-centered. Why not switch to the woman-centered one and scrap the other one?

There is a catch. Or, at first look some people think there is. The woman-centered economy is a subsistence-based economy. And that subsistence word scares people. Well, it scares people who are very dependent on or privileged by the male-dominated economy.

In The Subsistence Perspective, Maria Mies and Veronika Bennholdt-Thomsen point out that the village women of Bangladesh or others reliant on subsistence do not find subsistence scary. These Bangladeshi women understand that “what is important is what secures an independent subsistence.” (p. 3, The Subsistence Perspective). Mies and Bennholdt-Thomsen claim that the perspective of the Bangladeshi village women, a subsistence perspective, is desirable, even for people living with a great deal of privilege:

“The utopia of a socialist, non-sexist, non-colonial, ecological, just, good society cannot be modeled on the lifestyle of the ruling classes – a villa and a Cadillac for everybody… : rather it must be based on subsistence security for everybody.” (p. 4, The Subsistence Perspective)

Subsistence-based economies have sustained human life across countless millenia and continue to do so today. With the development of patriarchy, war, colonization and class, other types of economies were created, although subsistence economies endured. These new economies were based on an overclass accumulating wealth through various means such as taking land by force, slave labor, tribute, wage labor and taxation.

Today people’s relationship to subsistence differs based on how assimilated and privileged they are in the capitalist, colonizing patriarchy that now dominates the Earth. In general terms, those in the global North are likely to be well assimilated, feel a part of the dominant society and no longer have “an independent subsistence.” (“North” and “South” here refer more to the “developed” vs. “developing” world than to strict geographies. Even within a country, some groups may belong to the North and others to the South. [2]) In the global South many people are resisting, fighting to keep their own ways of life, including their subsistence economies.

Many of us would rather not support the male-dominated economy, but the thought of subsistence scares us or makes us uncomfortable. Yet … what an opportunity we have! We don’t have to wait for a feminist revolution!

My writing today is directed primarily to people in the global North. Many of us there would rather not support the male-dominated economy, but the thought of subsistence scares us or makes us uncomfortable. Yet … what an opportunity we have! We don’t have to wait for a feminist revolution! We already belong to a female-centered economy that can replace the male-dominated one.

By now, you are probably asking yourself: What is subsistence anyway? What makes subsistence a woman-centered economy?

What is Subsistence?

Mies and Bennholdt-Thomsen provide us with a simple definition of what they call “subsistence production” or “production of life” saying that this “includes all work that is expended in the creation, re-creation and maintenance of immediate life and which has no other purpose.” (p. 20, The Subsistence Perspective) The fact that subsistence economies have “no other purpose” is key to distinguishing the subsistence economy from capitalist and state run economies. That “other purpose” is profit, the creation of wealth for a few (mostly men) at the expense of the well being (and perhaps the survival) of the Earth and human society.

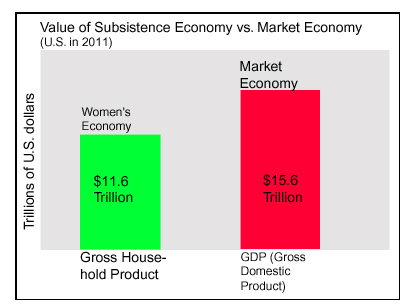

It is important to understand the importance and the size of the subsistence economy. Genevieve Vaughan recently discussed research from D. Ironmonger and F. Soupourmas showing that unpaid household work, called “gross household product”, would have cost $11.6 trillion in 2011, if wages had been paid.[3] Compare this to the $15.6 trillion figure for Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2011. Even in a highly developed country, the U.S., the subsistence economy is a multi-trillion dollar economy almost as large as the market economy! This economy is critical to the continuation of life and human society and women’s work is central to it.

It is important to understand the importance and the size of the subsistence economy. Genevieve Vaughan recently discussed research from D. Ironmonger and F. Soupourmas showing that unpaid household work, called “gross household product”, would have cost $11.6 trillion in 2011, if wages had been paid.[3] Compare this to the $15.6 trillion figure for Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2011. Even in a highly developed country, the U.S., the subsistence economy is a multi-trillion dollar economy almost as large as the market economy! This economy is critical to the continuation of life and human society and women’s work is central to it.

Despite the magnitude and importance of this woman-centered economy, over the past couple of centuries more and more women have joined the male-dominated economy as wage workers and business owners (while also continuing to do subsistence work). There are many reasons for this movement, including economic need, sexism, feminism and the much higher status accorded the male-dominated economy. There has been a “war against subsistence” at work here, as I’ll discuss in Part 2 of this blog. For now, please keep in mind that status is given and taken away by society and there is no reason to think that the work done for the “other purpose” of money in the male-dominated economy is in any way superior to subsistence work.

What Makes the Subsistence Economy Woman-Centered?

Creation of Life (Biological Reproduction): Women are the creators of human life. The work that only women can do bearing, birthing and nursing children is a key part of what makes subsistence a woman-centered economy. While men have a necessary role in biological reproduction it is fleeting and small compared to pregnancy and giving birth. The continuation of human life is utterly dependent on women, even where capitalist or state economies now sometimes play a (profitable) role through provision of reproductive technologies, doctors and hospitals.

Maintaining Life (Social Reproduction): Raising children is likewise critical to the continuation of human societies. Since this is social, not biological work, men often participate. Nonetheless, across countless societies and historical eras much of the work of nurturing and socialization has fallen to women. This is essential subsistence work carried out primarily by women and a key part of what makes subsistence a woman-centered society.

Across countless societies and historical eras much of the work of nurturing and socialization has fallen to women. This is essential subsistence work carried out primarily by women and a key part of what makes subsistence a woman-centered society.

It isn’t just idle speculation to say that it is mostly women raising children. The U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) collects data every year on how many “household hours” per week women and men spend doing child care (on average). Yes, women do much more child care! In 2018 we spent about 33 hours per week when unemployed and just a little less (30 hours) when employed.[4] The comparable numbers for men were about 23 household hours (unemployed) and 18 (employed). (In actuality, women and men with young children spend many more hours doing childcare than the BEA reports. The BEA numbers are based on averaging data from all U.S. households, including those that have no children or only older children who require much less care.[5]) Please notice that the BEA statistics do not have anything to say about the quality of childcare provided by men, as compared to women.

Maintaining life involves much more than socializing the next generation and women do much of this maintenance work too, even in the global North. You don’t have to have children to play a central role in running a household. For example, do you cook meals? Clean your house? Care for other members of your household when they are sick? Walk the dog? Do yard work? Sew buttons back on your clothes when they fall off? Keeping a household going can involve seemingly endless work and women do much of it! This is true even in households that have many modern “conveniences.”

Maintaining life involves much more than socializing the next generation and women do much of this maintenance work too, even in the global North. You don’t have to have children to play a central role in running a household. For example, do you cook meals? Clean your house? Care for other members of your household when they are sick? Walk the dog? Do yard work? Sew buttons back on your clothes when they fall off? Keeping a household going can involve seemingly endless work and women do much of it! This is true even in households that have many modern “conveniences.”

Women do even more work maintaining households in non-industrial societies where their livelihoods are more fully tied into the subsistence economy. This work can include tasks such as: processing and preserving of food from gardens or fields, carrying water, butchering, house building, weaving textiles, processing hides, making fishnets, manufacturing clothing, making pottery and many other crafts. In non-industrial societies women’s household maintenance work is likely to be higher where men have taken over more of the work of food production.[6]

Maintaining Life: Subsistence Production of Food: Despite all the work described above, in many non-industrial societies women can be heavily involved in subsistence production of food. In a 1986 article in American Anthropologist, Alice Schlegel and Herbert Barry documented the extent of women’s contribution to subsistence food production in 186 non-industrial societies. While men contributed more than women overall, in about half of the 186 societies women did over 35% of the food production. The researchers considered women’s contribution to be high when it reached this level (35%). Women were especially likely to make a high contribution to production in societies that used simple technologies to gather or grow plant food (high contribution in 70% of these societies). This is in stark contrast to societies based primarily in hunting of animals (high contribution in just 13% of these societies).[7]

We can’t include anyone’s production work from the capitalist economy (in jobs, as business owners) in these considerations as that work isn’t subsistence work and cuts into time available for subsistence work.[8] Today, women make up a major portion of the paid work force.[9] Still, some women in heavily industrialized societies do garden or keep chickens or other livestock for home (subsistence) use. According to the BEA, in 2018 men in the U.S. did a little more home gardening than women (The rough averages in the U.S. are 1 ½ to 2 ½ hours for men, ½ to 1 ¼ hours for women.)

We can’t include anyone’s production work from the capitalist economy (in jobs, as business owners) in these considerations as that work isn’t subsistence work and cuts into time available for subsistence work.[8] Today, women make up a major portion of the paid work force.[9] Still, some women in heavily industrialized societies do garden or keep chickens or other livestock for home (subsistence) use. According to the BEA, in 2018 men in the U.S. did a little more home gardening than women (The rough averages in the U.S. are 1 ½ to 2 ½ hours for men, ½ to 1 ¼ hours for women.)

Women in industrialized societies who want to participate more in the women’s economy could work fewer hours at jobs. Traditionally, women have been the gatherers of plants and were the inventors of agriculture. One avenue women could take to reclaim power would be in developing close relationships with and knowledge of the plant peoples. We could become gatherers, gardeners, seed collectors, tenders of the wild, herbalists or subsistence farmers. As has traditionally been the case in some subsistence economies, surpluses can be taken to market for barter or to obtain cash.[10]

Thanks to capitalist, colonizing patriarchy, we are facing an uncertain future where women and their local communities may need to take very seriously the need to focus on providing basic necessities like plant foods and medicine. The food sovereignty movement is important for the global North, not just the global South.

Subsistence is a Woman-Centered Economy

Let’s take stock of all the work creating and maintaining life that women do, as discussed here:

- Almost all the biological reproduction PLUS

- Most of the child raising PLUS

- Most of the household maintenance PLUS

- For nonindustrial societies, a very significant chunk of the food production.

Without women’s contributions there would be no subsistence economy and, indeed, no human society or life at all. Subsistence is a woman-centered economy!

In Part 2 of this blog, coming soon, we’ll talk about how choosing the women’s economy can bring the male-dominated economy to an end, while at the same time providing for humanity’s needs.

Footnotes

1. Lorraine Edwalds and Midge Stocker edited a very interesting anthology, The Woman-Centered Economy: Ideals, Reality, and the Space Between in 1995. This feminist anthology was more focused on creating and supporting a woman-centered economy within the existing market economy and did not have an emphasis on subsistence. There is the possibility of conjuring up multiple woman-centered economies, as I will discuss in Part 2 of this blog.

*****

2. “[I]nequality within countries has also been growing and some commentators now talk of a ‘Global North’ and a ‘Global South’ referring respectively to richer or poorer communities which are found both within and between countries. For example, whilst India is still home to the largest concentration of poor people in a single nation it also has a very sizable middle class and a very rich elite.” For more info.

*****

3. Genevieve Vaughan provided the $11.6 trillion figure for 2011 in her talk at the 2022 Maternal Gift Economy Conference. The reference she gave was for a 2012 article by D. Ironmonger and F. Soupourmas. I have not been able to locate that article as I do not have a university affiliation.

*****

4. The numbers I report come from my reading of the BEA graphs and are as accurate as I could make them, but please consider them rough figures.

*****

5. The BEA did not include detailed information on their methodology with their graphs. They say: “our estimates cover the entire economy, and most households do not have minor children present. According to the 2020 Annual Social and Economic Supplement of the Current Population Survey, 40 percent of households had children under 18. Only half of those (21 percent of total households) had children under 13, the ages that require the most direct child care.” If 79% of the households included in the BEA statistics do not have children requiring substantial amounts of care (ie. children under 13), then parents with young children must be doing far more work that the figures they provide and that I have referred to.

*****

6. See p. 145 in “The Cultural Consequences of Female Contribution to Subsistence” by Alice Schlegel and Herbert Barry. In American Anthropologist, V. 88, 1986. You can access the full article for free if you register as an individual on Jstor.

*****

7. See Table 1 on p. 144 for data on women’s contribution to subsistence in societies with various forms of subsistence. “The Cultural Consequences of Female Contribution to Subsistence” by Alice Schlegel and Herbert Barry. In American Anthropologist, V. 88, 1986. You can access the full article for free if you register as an individual on Jstor.

*****

8. See p. 14 in Ecological Revolutions: Nature, Gender, and Science in New England by Carolyn Merchant, University of North Carolina Press,1989.

*****

9. Labor force participation rates for U.S. women are 57% and 68% for men, according to the U.S. Department of Labor. According to the International Labor Organization the current global labour force participation rate for women is just under 47%. For men, it’s 72%.

*****

10. See p. 70 in “Money or Life? What Really Makes Us Rich” by Veronika Bennholdt-Thomsen. In Climate Chaos: Ecofeminism and the Land Question edited by Ana Isla, Innana Publications, 2019.